Expert Guide to Medieval Gardens

As a medieval historian by training it is apt that our first guide to garden history focuses on Medieval gardens - gardens created (or based on a style that was popular during) the 1,000 years from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries.

The image above of a Painted Lady Butterfly amongst the wildflowers was chosen because, as you will see, this is something that would have been seen in gardens a thousand years ago.

To begin with I wanted to very quickly set the scene. When it comes to the Middle Ages it may be more useful to talk of three periods, and therefore conceive of a series of inter-related garden styles. These are:

the Early Middle Ages - which began following the Roman withdrawal from Western Europe (in the early fifth century) and were characterised by movements of people and invasions - for example the Germanic peoples (such as the Angles and the Saxons) migrating across Western Europe, followed later by the Vikings; and further afield the Islamic empire was set up across the Middle East, North Africa and Spain

the High Middle Ages popularly characterised by feudal concepts of the lord of the manor and his peasants - think the years after 1066 and the Norman Invasion; but agricultural innovation, and (another) globally warm period, meant many did fairly well (a peasant could effectively be a small holder with up to 30 acres held upon the demesne of his lord and so could grow plenty)

the Late Middle Ages is a period characterised by both the values of chivalry and knighthood and by the impact of plague - the Black Death (1347 - 50 killed 1/3 of Europeans); states increasingly warred upon one another for power, peasants revolted (the most famous in 1381), and the Church was split by heretics as the battle for ecclesiastical power increased alongside the increase of the Church's wealth.

Generally speaking the English see that the Medieval period ended on 22 August 1485 - when Henry VII beat Richard III at Bosworth Field - with the Renaissance already in full swing on the Continent by this time.

What is a medieval garden?

This is an excellent starting point - the question as to what their purpose was. Are they primarily about dominance over nature? Creating a controlled space? Growing flowers? Growing food? Creating somewhere to sit safely outside? A place to relax?

In the Roman de la Rose, a French poem of 1230, Guillaume de Lorris uses the image of the garden as an allegory, and in doing so wrote about the image of the perfect garden; one additional element to those just mentioned being: “many songbirds were gathered throughout the garden: in one place were nightingales, in another jays and starlings, and elsewhere were great flocks of the wrens and turtle doves, goldfinches and swallows, larks and titmice…”

However in a medieval context I think we need to separate out different types of garden to help in their understanding:

Allotments - places to grow food

These obviously existed otherwise our ancestors would have starved or reverted to the life of the nomadic hunter-gatherer, but they were unglamorous and therefore are difficult to find evidence in the written sources. Food itself was mostly home-grown, or home raised for livestock, with the upper classes having access to more fruit (from trees), game meat, fish farmed in ponds and traded spices for their food. Those in towns also needed to be fed, and this was often done from gardens providing fruit and veg placed within or beside the town.

For evidence of this we can turn to the Capitulare de Villis - the earliest of the sources we have available for Medieval gardens; it was written in the Court of Charlemage, Holy Roman Emperor, in around 800, and is concerned specifically with the desire to ensure that his subjects were looked after; the final section dealt with what was to be grown by royal stewards in the gardens to supply the household of town leaders.

“Volumus quod in horto omnes herbas habant - It is our wish that they shall have in their gardens all kinds of plants:

lily, roses, fenugreek, costmary, sage, rue, southernwood, cucumbers, pumpkins, gourds, kidney-bean, cumin, rosemary, caraway, chick-pea, squill, gladiolus, tarragon, anise, colocynth, chicory, ammi, sesili, lettuces, spider's foot, rocket salad, garden cress, burdock, penny-royal, hemlock, parsley, celery, lovage, juniper, dill, sweet fennel, endive, dittany, white mustard, summer savory, water mint, garden mint, wild mint, tansy, catnip, centaury, garden poppy, beets, hazelwort, marshmallows, mallows, carrots, parsnip, orach, spinach, kohlrabi, cabbages, onions, chives, leeks, radishes, shallots, cibols, garlic, madder, teazles, broad beans, peas, coriander, chervil, capers, clary. And the gardener shall have house-leeks growing on his house. As for trees, it is our wish that they shall have various kinds of apple, pear, plum, sorb, medlar, chestnut and peach; quince, hazel, almond, mulberry, laurel, pine, fig, nut and cherry trees of various kinds.”

The list is mostly herbs, but also fruit from trees, flowers, as well as madder for dyeing and teasels for processing wool.

This document must however be interpreted with care. Charlemagne, like any ruler, did not issue a formal instruction to grow these plants because that is what was happening already. It is also important to note that he does not need to specify how these should be grown, which suggests that the knowledge of tending such a variety of plants was current among the gardeners of the time.

Therefore it may be reasonable to suppose that gardens were being filled with other things - perhaps "flowers of every variety"?

Monastic gardens -

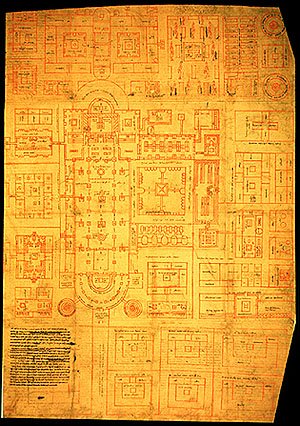

More evidence is available for monastic gardens. For example separate garden areas are shown on the St Gall plan - a drawing dated to around 820 and detailing a model plan of a monastery for the Benedictine Order of monks (from the Codex Sangallensis 1092 recto). This plan included:

A Medical Herb Garden (herbarium)

An Orchard

A Vegetable Garden (the cellarer’s garden)

A Cloister - restful green grass, possibly to relax the eyes of the monks working in the Scriptorum and surrounded by a covered walkway to avoid the rain

Similarly a plan dated to around 1165 of Prior Wibert’s Waterworks at Canterbury Cathedral shows that the presence of gardens in monasteries remained important - showing a Cloister, an infirmary garden (herbarium), and a vegetable garden (cellarer’s garden).

Gardens were therefore integral to monasteries - so they could feed and heal themselves and those who came seeking aid. Not all monastic gardening was concerned with the production of food though.

William Rufus, or William II, was third son of William the Conqueror, and he visited the nunnery at Romsey in 1092. He entered on the pretext of admiring the roses of the gardens, although by visiting the garden he allowed the young Edith of Scotland, whose mother was of the Saxon royal bloodline, time to disguise herself as a nun and so avoid being forcibly wed to him (as nuns couldn’t marry legally) which was the real reason for his visit. However the story is clear that admiring rose gardens was acceptable within society, even for the monarch, and that growing roses was acceptable in nunneries.

Herbers -

Away from Church the garden was a more earthly place, and popularly a setting for courtly dalliances. Representations of herbers in literature and associated manuscript art describe them as pleasure gardens that were:

Inward looking - the hortus conclusus

Sweet smelling - at a time of more fragrant sewers

Hidden - from prying eyes in a society seemingly more conservative than ours today

Specific details of how herbers were laid out can be pieced together from the written evidence, supported by the artwork. This allows designers to create an identi-kit medieval garden. An archetype for medieval gardens, whatever their size, can be gleaned from the description from Piero de' Crescenzi's Book on Rural Arts (Liber ruralium commodorum), written in 1305. This was the first time since the Romans where there is written evidence of gardening for pleasure; and by 1400 had been translated into French and Italian and in 1471 it was being printed to meet demand.

For Crescenzi a fine turf was central to the garden (physically and psychologically) - not the perfect green of today's lawns but grass studded with wildflowers, in what was described as a flowery mead.

The Unicorn Tapestries, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York which date from around 1500, show a profusion of botanically accurately depicted flowers that would have formed the flowery mead. These include: Pot marigold, Great Leopards’ Bane, pomegranates, wild orchid, bistort, thistle, madonna lily and carnation

To these garden descriptions should also be added additional elements from the design blue-print of the pleasure garden given in Roman de la Rose. These include:

a solid boundary "which was high and formed a square...to enclose and fence off a garden where no shepherd had ever been"

the importance of the inclusivity of wildlife as an essential element - a biodiverse garden - "...never was a place so rich in trees nor in singing birds."

Orchards and parks

I will now turn to the gardens of those with a little more wealth. In a larger garden orchards were particularly important. Advice from Crescenzi's Liber ruralium commodorum was:

“Plant lines of apples or pears in it, and, in warm places, lines of palms and lemons. Or plant lines of mulberries, cherries, plums, and lines of such noble trees as figs, nuts, almonds, quinces, and pomegranates, each one clearly in its own line or row according to type…[between the trees] treat the intervals as meadows and weed them often. Mow the meadows of the garden twice a year, so that they may remain beautiful.”

For Royalty (and bishops and abbots whose wealth rivalled that of kings) their gardens were simply on a much grander scale; a physical demonstration of their power and wealth, and of their ability to control nature. Grandiose herbers were placed within or beside castles - some becoming, or being incorporated into, the notion of the 'Pleasure Park' - a walled combination of herber, orchard, fish pond, and retreat. For example at Woodstock Henry I added to his Park a menagerie of wild animals, including lions, lynxes, leopards, camels and a porcupine (a clear difference to the pure hunting parks set aside for the Norman nobility); also at Woodstock, 100 years later, Henry III planted 100 pear saplings for their decorative effect (and also housed an elephant, a gift from King Louis IX of France in 1255).

Similarly the park at Hesdin in northern France was created in 1288 and famed for its tournaments as well as its menagerie, aviaries, fishponds, orchards and an enclosed herber called ‘Le Petit Paradis’. Crescenzi summarised royal garden pleasures as follows:

“a handsome palace…an enclosure for animals…a fish pond…certain bushes placed near the palace..into which are placed partridges, pheasants, nightingales, blackbirds, goldfinches, linnets, and all other kinds of singing birds…”

Gardens were also specifically designed for the enjoyment of Queens. The Queens of England tended to be European princesses before marrying English Kings in the forging of alliances across royal households. They often brought their own gardeners to England who presumably could then provide the horticultural feel of their home. Examples include Queen Eleanor of Castile who employed Aragonese gardeners to create a garden at King's Langley in Hertfordshire (she was 10 years old when she was married and so gardens to remind her of her home would have been important), or the Provencal gardener at Windsor employed when the Queen was Eleanor of Provence (Queen Consort of Henry III). At Rhuddlan Castle in Wales Edward I had another garden constructed for Eleanor of Castile, and her household, between July 1282 and March 1284 within the inner courtyard of the castle, where it would have been overlooked by the Royal apartments. Documents show that a little fishpond was also created, lined with four cartloads of clay brought from the nearby marsh and was set around with seats. The adjacent courtyard was laid with 6000 turves and the lawn fenced with the staves of discarded casks.

Existing Medieval Gardens

So far all of the gardens that have been considered are known only from what has been written or drawn - none survive to the present day. However there are some European gardens which survive from the Middle Ages. These however exist in Spain and as such share little in common with what we know of other European gardens. The Arabs invaded Spain after they conquered North Africa, and so their influence was introduced even though they did not manage to push further into Europe.

For example the Generalife Gardens of the Alhambra, which appear a little like Roman gardens, as well as the Court of Lions (also in the Alhambra). The Court of Lions has clear Persian influences such as the concept of charagh-bagh (this was a geometrical layout with water and crossed rills as the key features, the largest example today being the Taj Mahal).

Modern / medieval gardens

As modern gardeners we must remember that if the Medieval period ended in 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth, only about 21 generations separate us from them; the past may be a foreign country, but it’s not really that long ago and we haven’t changed that much in our perception of the world around us.

So what separates our gardens from the Middle Ages is simply time.

Gardens medieval or modern do include universally consistent features such as enclosure, nature, an array of plants, and green turf. The most important element however is the planting - the desired result of Medieval planting was described as “fragrant herbs and flowers of every type [that] not only delight by their odour, but their flowers also refresh the sense of sight by their variety.” The perennials in our borders today easily fulfil this requirement, sourced as they are from the vast range of plants discovered around the world in the intervening years, and with years of breeding for improved scent and colour by dedicated horticulturalists. So our gardens, filled with flowers, aren’t really much different to those of our ancestors.